I think several things about this video. The first is, a lot of people commit the gambler's fallacy when talking about 100 year or 500 year floods. On twitter, someone thought a 500 year flood was due (100% and guaranteed by the 500th year). But that's not true. A better way is to look in terms of a binomial distribution. This takes each year as a trial of a Bernoulli. For a 500 year span, we compute P = Bin(1/500, 500) in n+1, 1 - P(X ≤ n) for n in 0..3 as:

Chance of 1+ occurrences is ~63%

Chance of 2+ occurrences is ~26%

Chance of 3+ occurrences is ~8%

Chance of 4+ occurrences is ~2%

5+ is negligible. But even for a 500 year flood, a short time interval (better think a few number of trials), say 10 years (trials), the probability of 1+ successes is non-negligible.

Chance of 1+ occurrences is ~1.98%

Chance of 2+ occurrences is ~0.02%

If we look at a "100 year flood" for a span of 10 trials (years), it's:

Chance of 1+ occurrences is ~9.56%

Chance of 2+ occurrences is ~0.43%

Chance of 3+ occurrences is ~0.01%

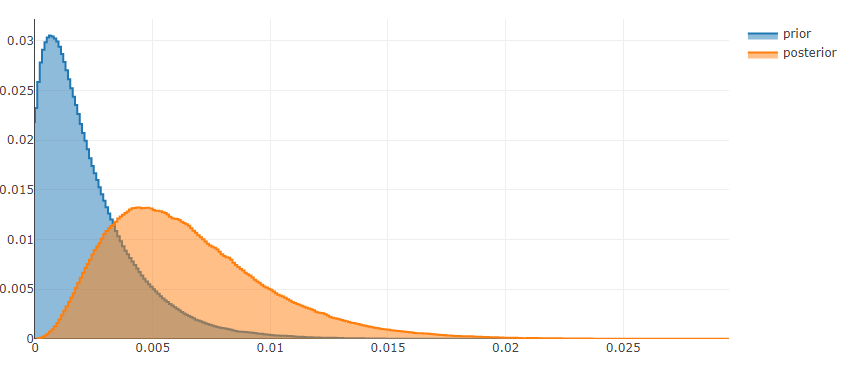

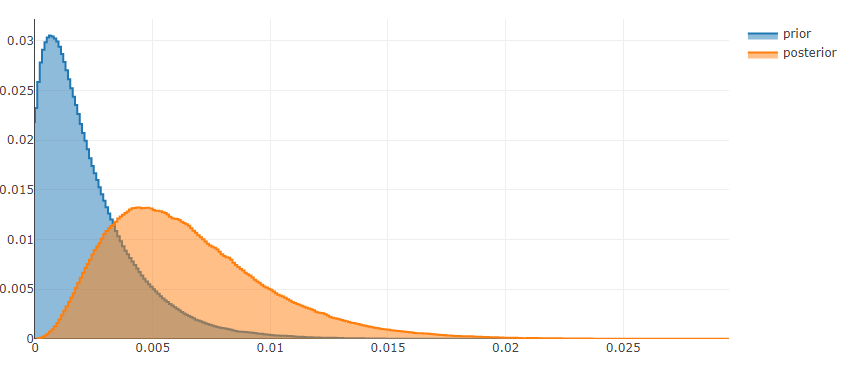

But I find not specifying any notion of uncertainty really dissatisfying. A better way to do this would be to specify a prior such as Beta(1,499) and then for each year, update with the number of occurrences of 500 year floods for the region. Over time, the distribution will shift, narrow or broaden reflecting changes in our uncertainty about what the parameter for our Bernoulli distribution should be.

Better yet, would be to model rainfall volumes directly, with say a log normal distribution (the video had a short snippet on normals but I assume this is due to their familiarity, rain fall is probably better modeled as log normal [1]). Then I might ask "what's the probability of seeing such an amount?" Again, I'd specify a prior over possible values for the parameters of the distribution to capture my uncertainty. With another model for the frequency of rain fall, I could then talk about N year floods except I would also be able to cleanly talk about N months, N day floods etc. And most importantly, I'd be able to parameterize my uncertainty. The upper end of the distribution could be used to plan for worst case scenarios instead of misleading people with useless point estimates.

I expect that over time, the number of formerly rare events will increase. The link between CO2 and the greenhouse effect has been known since at least the early 1900s. With melting poles, increased moisture and higher ocean temperatures, we can expect better fed hurricanes and tropical storms. Floods, heat waves, droughts and forest fires will be more common too. The general pattern of weather in places will shift as a result of change in the "parameters" deciding climate. This in turn will make weather prediction more difficult.

Tornadoes, hailstorms and even snowstorms—can those be linked to warming? The default answer would be to state or even over-state our uncertainty and bemoan our lack of data. I think that's wrong, optimizing for average case correctness is not always ideal. When lives and livelihoods are at stake, it's better to minimize regret and plan for the worst. Therefore, if ever I'm asked is this because of climate change? My answer will be yes and summarizing the previous recent paragraphs. Then I'd talk about what needs to be done, so people don't forcefully forget about it in hopeless despair.

[1] http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/1520-0450%281976%29015<0205%3ACMARS>2.0.CO%3B2