What does it mean for a system to be intelligent. Or Artificially so? The phrase Artificial intelligence is a contentious one, and for me, the cause of a not insignificant amount of frustration in discussions because everyone brings their own special meaning. However, looking closely at what it means to learn, it's clear that the notion of intelligence is not one of what but instead of what on. What's important and I believe often missed, is that there is no algorithm for intelligence, instead there are algorithms and whether they yield intelligence or not is task dependent.

Artificial intelligence is a broad term and according to Markoff [1], was coined by John McCarthy who wanted a name avoiding any association with Norbert Wiener's cybernetics. McCarthy also considered Shannon's preferred term of automata as having too much of a mathematical framing. Of the terms from that era, I personally favor complex information processing.

Until recently (circa 2005), Artificial Intelligence (AI) was a term to be avoided, in preference for machine learning, due to stigma from the overpromises and overreach of two decades prior. Today AI can mean anything from linear regression (basically just a drawn out addition and multiplication process) to The Terminator. It's a broad term and while I do not often view its use as wrong, there are usually more informative terms to use. Calling certain autocompletes AI, while not technically wrong, is in the same class of phrasing as referring to people as biological entities. This is true, people are biological entities but so are slime molds. Perhaps use a term with better specificity? Telling me there is a biological entity in front of me can require very different reactions depending on whether it's a tree, person, spider or elephant. Or tiger.

One common objection is: "that's not AI, that's just counting" or, "that's just algorithms". There are two observations I can make about this. 1) The assumption that animals are not limited to running (computable) algorithms. This may be true but it would come with a lot of baggage (why can no one factor 9756123459891243 in their head?). Things that a human can do but a computer cannot are few (things that a human can do but a computer cannot do well are numerous). It would be very surprising to find out humans spend all their hypercomputing ability solely on emotions and being "conscious". It's too early to require such a stance.

Observation 2) is that the algorithm is not all that matters, it also matters where said algorithm is being applied. Consider the following two examples: path tracing and Bethe's 1935 work on Statistical Theory of Superlattices.

Path Tracing is a way of computing lighting or illuminations so as to achieve a photorealistic rendering of a scene. At its most basic, a method known as importance sampling is used to estimate the integral of the equation that solves the light path calculations. That same technique, when employed on data, yields a form of approximate bayesian inference. One might complain that I'm cheating, and really, only a way of approximating integrals is what's shared. Furthermore, the algorithm is effectively making guesses on how the light likely behaved. But then again, that there should be such a close correspondence between efficient sampling and averaging of per pixel illuminance values and real photos is not obvious to me.

The link between learning and physics can be made even stronger when we look at how often bayesian inference and strategies developed by physicists to study systems with many interacting variables coincide (it's no surprise then, that thermodynamics turns up often, but it is by no means the only example). Ideas that are now showing up as important in both neuroscience and machine learning derived from work, such as mean field theory, done by physicists in the early 90s and late 80s. The broader historical pattern is physicists got there first—whether studying phase transitions or whatever it is they do—and computer scientists studying inference get there a few decades later.

Take the case of inference on tree structured distributions, computing the marginal distribution over the nodes can be done exactly using a message passing algorithm by Judea Pearl known as belief propagation (invented in the early 1980s). It turns out that none other than physicist Hans Bethe had similar ideas when modeling ferromagnetism [3] in the early 1900s. From [2]:

Notice, within the historical perspective, that the Bethe solution for the spin glass on a random graph was written by Bowman and Levin [44], i.e. about 16 years before realizing that the same equation is called belief propagation and that it can be used as an iterative algorithm in a number of applications. The paper by Thouless [299], who analyzed the spin glass critical temperature, implicitly includes another very interesting algorithm, that can be summarized by equation (78) where BP is linearized. The fact that this equation has far-reaching implications when viewed as a basis for a spectral algorithm waited for its discovery even longer.

Here the connection is non-trivial. It's not mere happenstance from using the same calculating tool but more fundamentally, the same core computation is in effect being performed. There's a key link in that the fixed point of belief propagation corresponds to stationary points of the Bethe free energy [4]. Unfortunately, the places where belief propagation works are limited to sparse graphs and trees, so sampling based methods are often preferred for practical inference. These too, find their origin in physics (monte carlo, gibbs sampling, variational mean field) but of particular interest are the variational methods.

It is proven via computational complexity methods that bayesian inference is intractable (we can never build a computer powerful enough to handle interesting/medium-large problems exactly). In particular, the normalizing constant is hard to compute (fancy way of saying divide so that it sums to one), because the are too many possible settings of parameters to consider. As such, we must resort to approximations. The favored way to do this is to approximate the target (posterior) probability distribution with another less busy one that's simpler to work with. It's also required that this approximation and our target diverge as little as possible. To do this, we search over a family of distributions for a distribution whose parameters are such that we get the best approximation of the target distribution (minimizing this divergence directly is also difficult so what happens instead is yet another layer of indirect optimization). When the space of models we are searching over is effectively continuous, this means searching over a space of functions for a function, given our requirements, which best represents our target. Hence the name variational methods—which derives from work done by 19th century mathematicians seeking an alternative more flexible grounding for newtonian mechanics.

The Calculus of Variations was mostly (initially) developed by the Italian mathematician/mathematical physicist Lagrange and Swiss mathematician Euler. The calculus began in the study of mathematical problems involving finding minimal length paths (that must satisfy some condition, most famously, what path takes the shortest amount given that our point is following the constraints of gravity).

The general format is, given some function that accepts functions and returns a number (a higher order function or functional), find a function that is optimal for our functional (and goes through these two points, say). The solution, one of: a maximum, minimum or flat resting stop, is known as a stationary point. The method of calculating this derivative on functions (since derivatives are themselves higher order functions, the types must be gnarly!) involves an analogy with the regular case. The functional must be stable to minor perturbations or variations. A perturbation is how the functional output changes with minor variations instigated by another function. When this is done with respect to some detailed energy calculations, one gets the Stationarity Principle of physics.

In nature we find, things like actions and paths are often taking minimal length paths, the relatively well known principle of least action. Unfortunately, this is a bit of a misnomer since quantum mechanics tells us that what nature really has is a principle of most exhaustively wasteful effort. QM tells us that all paths are taken and we only seem to see one path because only the stationary values correspond to the values (complex numbers) where phases did not cancel. As to why that is, I do not know but if it were any other way, if nature had to actively choose and hence know which paths were stationary, I suspect we would live in a very different kind of universe. Could we build computers that could solve problems our universe sized ones couldn't?

Nonetheless, the way mere humans have to calculate things is to seek out that critical point and to get that, we must use tools of optimization. These tools have turned out to be very general; so long as some internal structural requirements of the problem are satisfied, it can be used on that problem.

Parametric Polymorphic functions are algorithms that don't care to look at the details of the thing they are operating on, so long as some structural requirements are met. For example, a function that gives a list of permutations doesn't care if the list is of integers, movie titles or fruit baskets. The same reasoning can be used to partially explain why many ideas from physics are useful for building learning systems. Both physical objects and learning systems can be viewed as optimizing for some value, have a notion of a surface or manifold (for inference, space of models) that's moved along, a notion of curvature (in inference this is indirectly related to correlation) and distance (symmetric divergence between probability distributions) and a requirement to efficiently move along these surfaces seeking minimal energy configurations.

In both, there is a need to search for a function that acts as a good minimizer given our requirements. An object trying to minimize some quantity efficiently has only so many options to make. The correct way to move efficiently on a manifold constrains what operations you can perform. These algorithms and strategies are agnostic to the internal details of the problem; put in energy and physical things you solve physics problems. Put in log probabilities and solve learning problems. However, learning algorithms did not have to do this and in fact they do not have to follow these constraints. It's just that, if you wish to learn effectively, you'll behave in a way parametrically equivalent to physical systems bound by a stationary principle. Physicists often arrived first because they had physical systems to study, observe and constrain methods. Computer scientists arrive later, at the same spot, asking, how do we do this more efficiently?

If this seems a bit undramatic, don't be sad, as there is still a lot of mystery. The universe didn't have to be this way. Phases didn't have to cancel in such a way that we observe a seeming least action principle. Bayesian inference (and therefore all forms of learning, since they all reduce to approximating a probability distribution) did not have to be intractable. Or we could have lived in a universe with accessible infinities, for which computations difficult for us in our universe, were easy. But because of both these conditions, variational methods or similar have been important in getting correct results in both fields.

Nonetheless, it is a bit uncanny how often probabilistic inference on particular graphs structures often have a precise correspondence with a physical system. Consider, message passing to compute a marginal probability on one hand allows you to do inference and on something else, works out local magnetization. Why belief propagation and Beth Approximation ideas work as well as they do for computing a posterior probability distribution (a knowledge update) is not well known. Part of the uncanniness is of course, a lot of thermodynamics is also inference but that is less than a satisfactory answer. The boundary between entropy and information and as such, energy is very fuzzy for me. In a future essay I'll look more into this but for now, I'd like to look at variational free energy and what it says about the brain's computational ability.

Variational free energy is an informational concept (negative model log likelihood for the data) that slots into where (IIUC) Gibbs free energy would fit into for a physical system. In an inferential system with an internal world model, variational free energy does not tell you about the physical energy of the system. It instead tells you how well your internal model matches your sensory inputs or data inputs or historical signal inputs. You want to minimize any future discrepancies as much as possible but don't want to drift too far from your prior experiences. The concept of variational free energy finds much use in machine learning and neuroscience. The better the model, the lesser the free energy on our variational approximation and the better we are doing. In other words, the less surprises we are having.

Here's what's key. As I point out above, variational methods are an approximation due to computational limitations. If we find that it is in fact true that the brain is also forced to optimize on some variational bounds and no better than a mere pauper Turing machine (resource bounded) , this too would be very suggestive that the brain itself is not just computable but bound by computational complexity laws!

The link between learning and thermodynamics goes deeper than simple correspondence however. In [5], Friston et al also point out how the brain will also operate to minimize its Helmholtz free energy by minimizing its complexity (giving less complex representations to highly probable states. You should not be surprised then, when we find expertise means less volume in highly trafficked areas or less energy use for mental processing of well understood things). Similarly, in the very interesting [6] Susanne Still shows that any non-equilibrium thermodynamic system being driven by an external system must alter its internal states such that there is a correspondence with the driving signal and coupling interface. This is necessary to minimize wasteful dissipation. Therefore, it must have something of a memory and state changes will implicitly predict future changes in order to operate efficiently, maintaining favorable current states. As such, efficient dynamics corresponds to efficient prediction.

Evidence for the importance of energetic efficiency is furthermore found in biomolecular machines that approach 100% efficiency when driven in a natural fashion: the stall torque for the F1-ATPase [26] and the stall force for Myosin V [27] are near the maximal values possible given the free en- ergy liberated by ATP hydrolysis and the sizes of their respective rotations and steps. These and many other biological functions require some correspondence between the environment and the systems that implement them. Therefore the memory of their instantiating systems must be nonzero. We have shown that any such system with nonzero memory must conduct predictive inference, at least implicitly, to ap- proach maximal energetic efficiency.

We thus arrive at an interesting separation. All systems we call alive (right down to bacteria) concern themselves with both variational and thermodynamic free energy but digital AIs only concern themselves with the variational concept.

In summary, those who reject certain algorithms as AI are making a fundamental mistake by assuming that the algorithm is what makes an AI. Instead, it's where the algorithm is used that matters. A simple dot product (something no more complex than 5 * 3 + 6 * 2) in one condition might be a high school math problem or find use in lighting calculations in a graphics engine. In another context however, it might compare word vector representations of distilled co-occurrence statistics or encode faces in a primate. We should expect then, that an AGI or an ASI will consist of narrow AI joined together in some non-trivial fashion but still no different from math.

I additionally pointed out the correspondence between inference and physical systems is not so surprising when viewed as aspects of something more general, analogized with a polymorphic function. But it is nonetheless not obvious why things ended up as such. Computational complexity limits and energy limits turn up at the same places surprisingly often and demand similar dues of informational and physical systems.

The link goes even deeper when we realize that predictive efficiency and thermodynamic efficiency of non-equilibrium systems are inextricably linked. Not just that brains and predictive text autocomplete should count as performing inference but also, simple biological molecules. In fact, these systems might have gotten as complex as they did in order to be more effective at prediction, in order to more effectively use a positive free energy flow for say, replication or primitive metabolism.

I can now finally put forward a definition for what AI is. An AI is any algorithm that has been put to the task of computing a probability distribution for use in some downstream task (decisions, predictions), a filter which leverages the structure of what it is filtering, or performs a non-exhaustive search in some space. Autocomplete that enumerates alphabetically is not intelligent, Autocomplete that predicts what I might type next is. From the context of Intelligence amplification, an intelligent algorithm is any system that works cooperatively to reduce working memory load for the human partner.

In a future post I'll look into what algorithms the brain might be running. This will involve synthesizing the following proposals (what they have in common, what they differ in and how plausible they are): Equilibrium Propagation, Sleeping experts, approximate loopy belief propagation, natural evolution strategies and random projections.

Weak AI - Weak AI are programs that learn how to perform one predictive or search task very well. They can be exceedingly good at it. Any AI is certainly a collection of weak AI algorithms.

Narrow AI - A synonym for weak AI. A better label.

Machine Learning These days, it's very difficult to tell apart machine learning from Narrow AI. But a good rule of thumb is any algorithm derived from statistics, optimization or control theory put to use in the service of an AI system, with an emphasis of predictive accuracy instead of statistical soundness.

GOFAI - This stands for Good old fashion AI's, expert systems and symbolic reasoners that many in the 1970 and 80s thought would lead to AI as flexible as a human. Led to the popular misconception that AIs must be perfectly logical. Another popular misconception is that GOFAI was a wasted effort. This is certainly incorrect. GOFAI led to languages like lisp, prolog, haskell. Influenced databases like datalog, rules engines and even SQL. Knowledge graph style structures underlie many of the higher order abilities of 'Assistant' technologies like Siri, Google now, Alexa, Cortana, and Wolfram Alpha.

Furthermore, descendants are found in answer set programming, SMT solvers and the like that are used for secure software/hardware and verification. An incredible amount of value was generated from the detritus of those failed goals. Which should tell us how far they sought to reach. Something else interesting about symbolic reasoners is that they are the only AI based system capable of handling long complex chains of reasoning easily (neither deep learning nor even humans are exceptions to this).

True AI - This is a rarely used term that is usually synonymous with AGI but sometimes means Turing Test passing AI.

Artificial General Intelligence - This is an AI that is at least as general and flexible as a human. Sometimes used to refer to Artificial Super Intelligence.

Artificial Super Intelligence - This is the subset of AGI that are assumed to have broader and more precise capabilities than humans.

Strong AI - This has multiple meanings. Some people use it as a synonym for True AI, AGI or ASI. But others insist, near as I can tell, only biological based systems can be strong AIs. But we can alter this definition to be fairer: any AGI that also maximizes thermodynamic efficiency by maximizing energetic and memory use efficiency of prediction.

AI An ambiguous and broad term. Can refer to AGI, ASI, True AI, Turing Test passing AI, AI or Clippy. Depending on the person, their mood and the weather. Ostensibly, it's just the use of math and algorithms to do filtering, prediction, inference and efficient search.

Natural Language Processing/Understanding The use of machine learning and supposedly linguistics to try and convert the implicit structure in text to an explicitly structured representation. These days no one really pays attention to linguistics, which is not necessarily a good thing. For example, NLP people spend a lot more time on dependency parsing when constituency parsers better match human language use.

Anyways, considering the amount of embedded structure in text, it is stubbornly hard to get results that are any better than doing the dumbest thing you can think of. On second thought, this is probably due to how much structure there is in language on one hand and how flexible it is on another. For example, simply averaging word vectors with some minor corrections does almost as well and sometimes generalizes better than using a whiz bang Recurrent Neural Net. The state of NLP, in particular the difficulty of extracting anything remotely close to meaining, is the strongest indicator that Artificial General Intelligence is not near. Do not be fooled by PR and artificial tests, the systems remain as brittle to edge cases as ever. Real systems are high dimensional. As such, they are mostly edge cases.

Deep Learning These days, used as a stand in for machine learning even though it is a subset of it. Such a labeling is as useful as answering "what are you eating" with "food". DL, using neural networks, is the representation of computer programs as a series of tables of numbers (each layer of a Neural Network is a matrix). A vector is transformed by multiplying it with a matrix and applying another function to each element. A favored function is one that clamps all negative numbers to zero and results in piecewise function approximation. Each layer learns a more holistic representation based on the layers previous, until the final layer can be a really dumb linear regressor performing nontrivial separations.

The learned transformations often represent conditional probability distributions. Learning occurs by calculating derivatives of our function and adjusting parameters to do better against a loss function. Seeking the (locally) optimal model within model space. Newer Neural networks explicitly model latent/hidden/internal variables and are as such, even closer to the variational approach mentioned above.

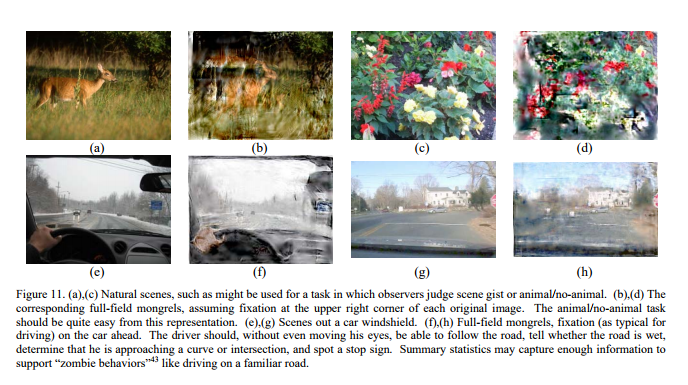

Speaking of latent variables, there is an unfortunate trend of obsession about the clarity of model generated images. Yet quality of generation does not necessarily equate with quality of representation. And quality of representation is what matters. Consider humans, the majority of our vision is peripheral (we get around this by saccading and joining small sections together). Ruth Rosenholtz has shown a good model of peripheral vision is of capturing summary statistics. Although people complain that the visual quality of variational autoencoder is poor due to fuzziness, their outputs are not so far from models of peripheral vision.

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cb87/dfabb88f37114c4ca6c64ff938ae32f00c74.pdf

The obsession is even more questionable when we consider that internal higher order representations have lost nearly all but the most important core required for visual information. Lossy Compression is lazy = good = energy efficient. Considering their clear variational motivation and the connection to the Information Bottleneck Principle, I feel it a bit unfortunate that work on VAEs has dropped so, in favor of Adversarial Networks.

[1] Page: 67 | John Markoff, Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

[2] Page: 40 | 1511.02476.pdf

[3] http://rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/royprsa/150/871/552.full.pdf

[4] Page 1 | WellerEtAl_uai14.pdf

[5] Page: 9 | Information and Efficiency in the Nervous System

[6] Page: 4 | 1203.3271v3

Path traced image