Home | Articles & Essays | Lab.Project Int.Aug | Project Int.Aug

Note: 12/20/2015 | This piece was written without ever having read Clark's and Chalmer's Extended Mind thesis or anything like it. Indeed, at that point, I did not know intelligence amplification or augmentation was a concept with a long and rich history.

I would like to talk about how some of our assumptions hinder our ability to design robust software experiences and how that negatively impacts our development as a species. In particular, our assumptions on human memory.

I am surprised that in deciding what a memory is, people choose to make a distinction about where a memory is stored – why should something be a memory only if it is stored in your head? Even people who use the term exocortex typically use it in a tongue in cheek manner. If I were to say: “wait let me try and remember” and pulled out a device connected to a cloud store and then searched for whatever, most people would not call that act as part of remembering. They would find it strange to call something stored on a distant computer your memory. But in deciding whether a memory (or anything) is yours – distance should not matter so long as only you can determine its state; encryption is one way, surrounding your brain with a skull is another.

Allowing shared memories is another option. One can argue that it is begging the question to assume a memory can only be personal. Indeed, there are already counterexamples. Currently the closest to shared memory is unreliable reconstructions that are projections of shared events. So in a way there is a limited precedent of multiple people having access to the “same memory”. Just because other people can now more faithfully access and represent a part of your collective memories does not make it any less of a memory.

I think part of the problem is that few people have taken the time to think about what a memory is. And part of the reason for that is because we don’t really know what memory is. We know that it involves changes in synaptic distributions and weighting, as well as possibly methylation like effects (could get away with saying epigenetic). And that similar memories tend to wire together. We also know that at least some memories are similar to JPEG (decomposition in terms of sparse representations for later reconstruction) with crappy floating point (each reconstruction introduces some drift hence usefulness of repetition). There are a lot of leads but the picture is still murky. What we do know is that when a memory is formed, some kind of physical encoding is represented by neurons which are triggered together by some kind of associative pattern matching process. But even this high level almost empty phrasing is not something most people will pause to contemplate (this is not bad per se, people can pick their priorities). So what we have is that because most people don’t stop to think about memory in order to reorder the concept, they form all sorts of hidden unproductive associations that tie down the notion arbitrarily.

Generalizing, a memory is data which has significance to some composite entity and is physically encoded using some mechanism that allows some level of permanence to that state and some manner by which this state can be seen as connected to patterns that are nearby by some metric. Forcing that metric to be distance or based on the specific substrate of proteins seem pretty arbitrary. Storing is only half the process though. We also need recall. Recall is a reconstructive process which using stored key bits, allows one to come as close as possible to representing the original state of information that triggered the encoding process. It is arbitrary to declare the limit to be the pattern matching process of neurons and disallow this process to extend into encapsulating pattern matching algorithms on computer chips outside (or inside) the brain. We allow the flow of triggers to not only be limited to ion gates but to also allow muscle contractions and transistors regardless of their relative position to our brain – so long as they can transmit signals which aid in the reconstruction of the original set of data. Writing on paper and later looking it up is a form of this. Storing information on computers and later searching for it is another. As the ease with which fuller more faithful memories can be formed increases and the latency decreases, our reach and intelligence also increase. Paper and a manner of encoding (language) allowed complex structures like civilization to exist. Computers accelerate the rate with which we can improve on improving.

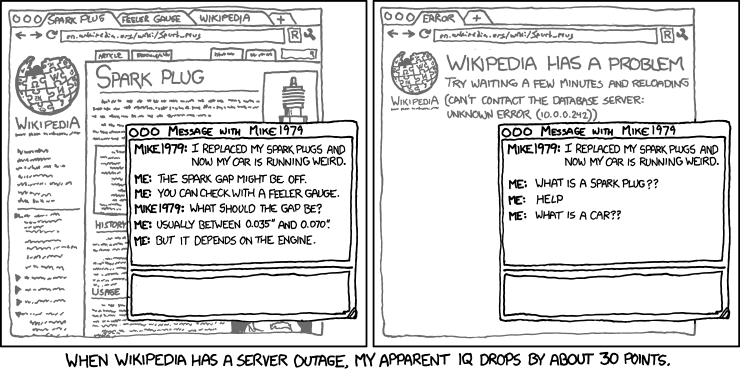

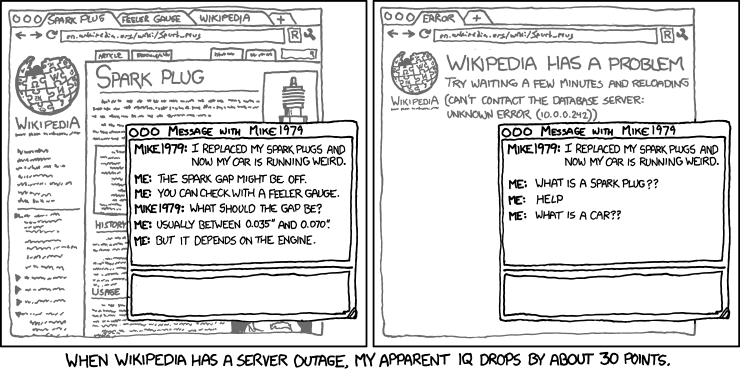

The key point I am trying to make is that by dropping the assumption that a person’s memories can only be stored with neurons located inside their skull, we can start to think of how to improve the current state of affairs and the consequences of this. How can we design better tools and process to enhance this flow of what is really a more general form of learning and recall? And what if we generalize the notion of thought and mind? It is clear that current metaphors of files, documents, etc. are not up to par. What unnecessary frictions are we creating by choosing the wrong metaphors and delineating random boundaries? Giving up on arbitrary biases allows for simplification and elegance. With such changes we can think thoughts and come up with things that would never have been accessible otherwise. As Alan Kay says, a change in perspective is worth 80 IQ points.