Are RNNs Turing Complete? Is a question that has bothered me for some time. I still do not have an air tight resolution but my general belief is no, not really.

This issue came to the fore today for me, when the author of Keras (François Chollet), a popular wrapper atop the Tensorflow deep learning library, stated that matrix multiplication is insufficient to capture general intelligence. He also made two confusing statements: Long Term Short Term Memory Networks are not Turing complete but ConvLSTMs are. Recurrent Neural networks have been proven to be Turing complete and LSTMs generalize these, therefore LSTMs should also be Turing complete (the LSTM should learn not to use the "forget" gate if it is getting in the way).

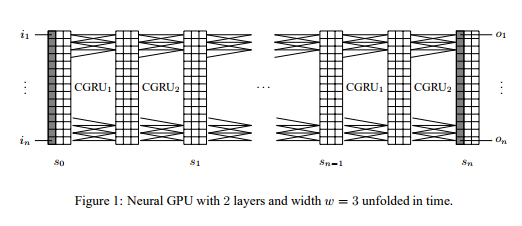

Convolutional nets are a simplification of Multilayer Neural networks—that is, they invoke several structural biases such as translational invariance and how to coarse grain to reduce the number of parameters to be learned—therefore, it is difficult to see what they could add to LSTMs that they lost in comparison to RNNs. This is answered in [2], where the authors point out a close correspondence between Neural GPUs and Convolutional LSTMs. Neural GPUs extend Gated Recurrent Units (a simplification of LSTMs) to operate on state that is a 2D grid of vectors, which are then convolved over across time steps. This allows for more parallel computation and efficient implementations.

They draw a correspondence with 2D discrete cellular automata, as a class with similar computational power. While it seems likely that Turing Complete algorithms can be less elaborately represented in this architecture, the learnability of more complex many step algorithms remains strongly in doubt. They mention difficulty multiplying decimal numbers as well as scaling to larger instance sizes of say, binary addition problems.

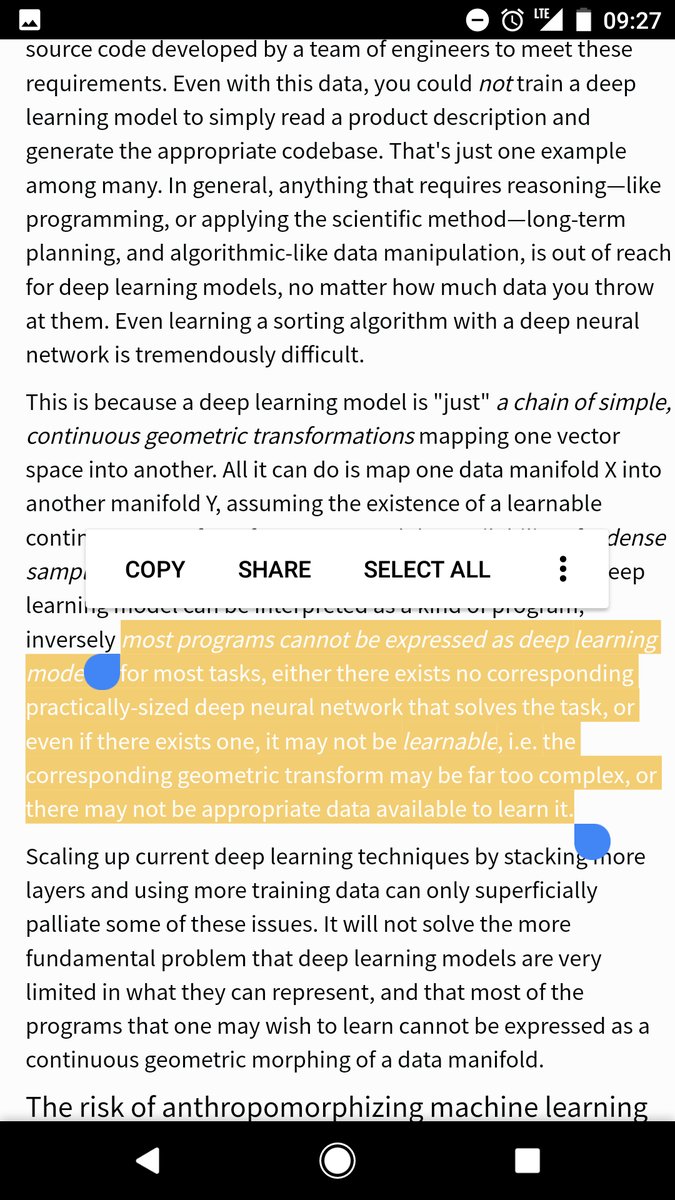

Those trivialities aside, I actually agree with his statement from the tweet:

Before discussing his important and very likely true point, it's worth looking at the proof of the Turing Completeness of RNNs and why I don't think it's of practical consequence.

I found the proof difficult to unpack—it's dense, there's lots of notation and even outmoded terminology. It seems like it would take me days to fully understand it. But I could extract a sketch:

It is known that two Push Down Automata (a Finite state machine extended with a stack) to simulate both sides of a Turing Machine, are Turing Equivalent. The proof then sets up a dynamical system which can simulate two PDAs. The task is to simulate that system with a neural net. At this point, it's worth pointing out as the paper does, that Minsky proves the existence of a Universal Turing Machine with just 7 control states and a 4 letter tape. Thus, their construction only needs a relatively small number of states to be universal.

To complete the proof, they show the composition of a series of functions (defined over the rationals) computes the dynamical system of interest. Their recurrent neural network is shown to match this. However, the construction is very particular. For example one layer computes:

\(\sigma(4q_i - 2\zeta[q_i] - 1 + \sum\limits_{j=0}^s \sum\limits_{i=1}^{16} c_{ij}\sigma(v_i \cdot\mu) - 1)\)

where ζ is a thresholding function over the subset of rationals expressible as a particular kind of Cantor set. The method also seems to need some post processing in the form of re-ordering and such like. It's an elegant argument (which I don't even fully understand), but what is clear is that this recurrent net bears little resemblance to systems as used in practice. I daresay it's closer to cellular automata than LSTMs. For example, suppose I showed you a rule 110 automata and said: "you know, in principle it is possible to encode an AI in this flashing pattern of black and white dots that would want to harvest humans for carbons". You'd probably say "neat!" and promptly forget. It's not the kind of observation that comes with any practical consequence.

Another (and the easiest) objection to make is that the proof requires rational weights while most neural networks utilize 32 bit (and soon 16 bit) floating point numbers as weights. But a similarly easy objection is that the neural nets can learn a good enough approximation. I doubt it—the rationals require a particular and precise form, else the memory would not be dependable. The nets would need to learn corrections atop the structure and stack operations. This seems unlikely.

The other objection is there's no known method to learn on these nor any guarantee that your training will ever converge on such an architecture. Simulated annealing over arbitrary network architectures might get there first—and it only converges giving an infinite amount of time. A response in turn might be that the proof is not necessarily the only form a Turing Complete RNN can take. The proof only shows that such an encoding is possible and it might therefore be feasible that RNNs could arrive at easier representations. This is plausible and it leads me to my third objection, pointed out and explained here by Edward Grefenstette. The memory vector has finite state and newer inputs saturate such that RNNs only learn short ranged correlations and are not much more powerful than a Finite State machine.

Most sequence to sequence architectures come in encoder/decoder pairs. Encoders are folds and decoders are unfolds. A fold is a function that structurally recurses over and deconstructs an input.

fold (+) 0 [1,2,3] = 6.

fold (*) 1 [1,2,3] = 6

fold ((s, c) -> c + s) "" "123" = "321"

In the last example, the s stands for the string built so far and would correspond to the "hidden state" or memory of an RNN.

An RNN is:

(A List of some kind) ▷ fold ((h,x) ⇒ \(W_{hx} x + W_{hh} h + b_h\) ▷ Vector.map tanh) [0,0,...,0]

Wxh and Whh are matrices which together represent whatever function so far best minimizes error with respect to some loss function. If the function above was calculated with respect to say, dual numbers—automatic differentiation—then one gets derivatives for free, which one can then use to adjust the weights; hence, learning. There is a great deal more plumbing to actually make things work but the above captures the essence.

The decoder is more of an unfold, which constructs possibly an infinite stream given some initial state:

unfold (state -> Maybe(Output,state')) initial_state

Where the maybe terminates given an appropriate condition. Encode/Decode, such as in language translation (encode english, decode japanese) then becomes a fold ∘ unfold style computation.

Since the internals are just affine matrix transformations and the general structure is one of hylomorphisms, I think RNNs are at most learning total functions. The (encoder) RNN is searching for a function like (+), that combines the current state with the new input. This is a good thing—learning arbitrary programs would make training undecidable (humans run some parts in parallel—it's feasible for a human to spend their entire runtime searching for structural regularities—with those processes never terminating, until a segfault).

If we bring limited memory back into the picture, we see that the number of bits representable by state is limited by the size of the vector. Since the state is degraded for distant inputs, the search will focus on functions that depend on a relatively short history. As a rough analogy: in the above where we were folding over the characters of a word, imagine instead if the string was of limited size and we wanted to build patterns based on the previous patterns. We would be limited in what we could express.

The LSTM makes the best out of a crappy situation by learning what to evict and what to keep, learning longer (but still limited) range correlations. LSTMs might be close to Pushdown automata with a faulty stack. So RNNs I think, while probably in principle (co)inductive, learn only a subset of that class of functions. The subset which are smooth and well enough behaved and that also satisfy the low weight prior of stochastic gradient descent.

RNNs don't just have to learn good representations, they also have to learn operations and algorithmic transformations on the data. This means trading feature engineering time for more Joules and longer, more complicated training regiments.

The combination of few assumptions, powerful model class and large complicated space all but guarantees the requirement of a large amount of data and energy spend. Several steps have to be learned to make progress and this quickly gets very complicated by the time high level concepts are the target. This, in my opinion is wasteful—even humans come with certain inductive biases. Finding the right combination of not overly specific hand engineered features seems like one of the many things which will need to be discovered to arrive at more powerful learners.

All together, the above highlight my strong skepticism of the Turing completeness of RNNs. The worries that they'll replace everything, including humans, by 2025 are verging on nonsensical.

[1] https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1759/4df98c222217a11510dd454ba52a5a737378.pdf